ROSENWALD’S FOURTH SHEET

by Franco Pratesi, 24.11.2011

When the great Michael Dummett (apparently he has been a great author in several fields, but let me limit here this acknowledgement as a card historian, whom I know better) wrote his fundamental book(1), it was impossible for him to recognize the Rosenwald sheets as parts of a minchiate pack. As far as he could know the situation in 1980, no minchiate could exist as early as the sheet in question, generally considered to belong to the end of the 15th century or the beginning of the 16th. On p. 403 of the book mentioned he thus states: "This is certainly not a Minchiate pack, since it has only twenty-one trumps. … It therefore seems probable that the set represents an early form of that standard pattern for the Tarot pack on which the Minchiate designs were later based, or some closely related pattern."

After several findings, it is now easy for me to see here nothing less than a part of a minchiate pack. My greatest interest however is not focused on the three known Rosenwald sheets, but on the fourth one, which remains unknown to the point that I am not aware of anybody having described it up to now. Of course to describe something unknown requires a remarkable degree of imagination, and I will actually use mine in the following, on the basis however of some concrete reflection.

The Rosenwald Tarot

Before entering into "my" description, let us examine the known part of the sheets. Here we already find something puzzling, beginning with the sequence of the figures, which show some mistakes both in their positions and numbering.

Actually, several experts have already pointed to Florence in commenting the style of the figures, and the order of the sequence, but often this occurred with the addition of a question mark or the interpretation as a standard Florentine tarot pack, in which the standard attribute should be better related to the 78-card tarot than to its Florentine location. Something I could add on the iconography, but this I leave with pleasure to the many experts.

There are only a couple of general points that I wish to comment on here. The first is represented by dimensions. The sheet shape, to begin with, is 280x435 mm (Leinfelden), which corresponds to a rather common kind at the time. How many cards can you produce with such a sheet? It obviously depends on the dimensions of the individual cards (here 51x87 mm), which however should respect simple ratios with the sheet dimension, in order to use the expensive paper then available in the most efficient way.

In this case (I could not ascertain whether this could represent a standard or was instead an isolated case) the ratios are 3 for card height and 8 for card width. Clearly, passing from 3 to 2 or 4 for height ratios would give too unusual heights; probably, passing instead from 8 to 7 or 9 for the widths could still provide acceptable dimensions for the cards. On the other hand, producing the same 24 cards with the alternative system of 6 rows of 4 cards could have required a sheet with different dimensions. In any case, the fact that one sheet is used for producing 24 cards will require some comment later on.

A second point is whether all the three sheets belong to the same pack. It seems they don’t, as one can deduce from a detailed inspection by Ross Caldwell, with results reported below.(2) "The divisions between the cards on the trump sheet are single black lines, while the divisions on the others are double narrow lines. The style of the woodcut appears to be different as well - the lines of the court card sheet seem finer. Moreover, the suit symbols that are common between the trump sheet and the court card sheet are different - the Cups are very much more ornate in the court sheet (three protrusions and inner designs on the court cards, compared to the two protrusions and blank inside on the Queen in the trump sheet), the Swords on the court sheet have a pointed 'wave' in the middle of the hilt, compared to the straight bar on the Queen of the Trump sheet; finally, the Coin of the Queen in the trump sheet has a 'flower' band in the middle register of the circles, while the court cards lack it. In other words, the Queens and their suit symbols are very plain and different from the court cards in the other sheet."

Nevertheless, I am trusting in a given standardization already existing for these packs, and will deal with these three sheets as if they belonged to the same pack. Actually, I accept the idea that a number of packs greater than one is involved in Rosenwald sheets, but see this as a support of the validity of the 3x8 pattern under examination.

After considering the general points, we can pass to the observation of the individual sheets. The preserved sheets are three in Washington and one in Leinfelden. Let us begin with the two ones that are only in Washington, which I label as Sheet 1 and Sheet 2.

Sheets 1 and 2

I examine all the sheets from bottom right to top left, exactly in the contrary direction with respect to our common way of reading the page of a book.

Sheet 1 is the simplest of them all. The bottom line ha 2 to 9 of Batons (B), the middle line 2 to 9 of Coins (C), the top line 9 to 3 of Swords (S, note that the 2 is displaced one step to the right, between 4 and 3, the first of several “mistakes” in the positions of these cards). One thinks immediately to the different order in taking power of these cards in the different suits, but this again does not correspond to a correct position of the cards. As a matter of fact, the order in the game is ascending for Cups and Coins, whereas it is descending for Swords and Batons: here we have instead together Batons and Coins, and Swords together with the Cups suit of the next sheet.

Sheet 2 has in the bottom line the continuation of Sheet 1: Cups from 9 to 2. The middle line has in the first half the four Knights (in order B,K,S,C) followed by the four Kings (C,K,S,B). The top line has in the first half the four Jacks (C,K,S,B – the two first ones feminine here as in other packs of the time) followed by the four Aces (C,K,B,S).

We can make a pause at this point, after examining two complete sheets. With these two sheets, what do we have and what is still missing? We have 48 cards, and this is a result that cannot be questioned. Was this already a complete pack of cards? I cannot assert this with absolute certainty. Of course, we know that for centuries this has been the commonest pack for Spain, and Spanish cards had a remarkable influence on several Italian packs too. Another common pack in Spain and even more so in Italy has been the 40-card pack that can be derived from this item by simply eliminating the four 8s and the four 9s. On the other hand, if one wants to reach a complete 52-card pack, all four 10s are clearly missing here, but I don’t know how much this "complete" pack was actually used.

Sheet 3

Now we are ready to attack the more complex Sheet 3. In principle, we are fortunate to have two instead of only one remaining Sheet 3. Since however the contribution of the Leinfelden specimen brings more doubts than certainties, let me first consider only the Sheet 3 from Washington.

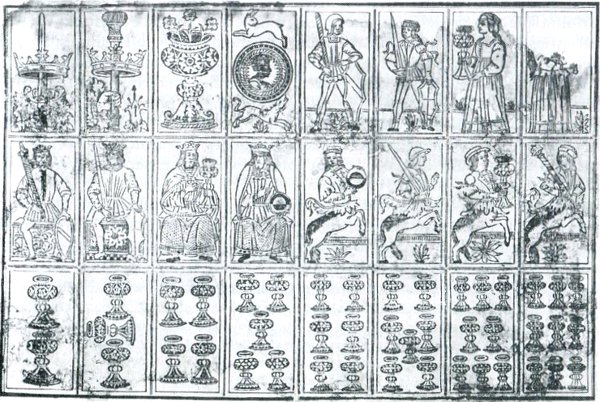

After examining the two first sheets we would expect to see here the 10s required for completing the pack for other possible games. With some surprise, we cannot find any 10 in Sheet 3! Sheet 3 is clearly addressed to a triumph production and we know that in this case the already found three court cards are not enough. In addition to Jacks, Knights and Kings, in a triumph pack (and also in some early common packs) we also have Queens, as a whole thus 16 court cards instead of 12. The problem is that we find only three of these four additional cards here, the Queen of Batons being absent.

Let me examine the sheet as before, beginning from bottom right to up left. Let me also number the 24 places in the mentioned succession as A,B,C, followed by 1 to 5 in the bottom row, 6 to 13 in the middle one, 14 to 21 in the top one. A,B,C are the three Queens (in the order K,S,C, with B missing). Then we find in the bottom row the triumphs with Roman numbers I to V. In the middle row the first 6 cards are also numbered in the same way (with number VIIII erroneously repeated as number VIII, and number XII instead of XI marked for the Eremita), then the same series continues with unnumbered figures, two in the middle row, eight in the top one.

A comment by Lothar Teikemeier on these mistakes in the numbers of the triumphs may be useful.(3) He observes that these numbers appear to have been drawn directly on the cards, instead of being already present in the woodblock. He suggests moreover that this way of production could provide the cardmaker with a useful tool to adapt his packs to their various possible destinations, including places where different systems were used for ordering the triumphs. In particular, the highest unnumbered triumphs could thus be used both in tarocchino bolognese and in minchiate (in the latter case, they had much higher nominal numbers).

Comparison between the two copies of Sheet 3

About the Leinfelden sheet, I have checked the literature and even asked the Museum for information. The director, Dr. Annette Köger, kindly answered that the sheet is hardly damaged and that no improvement can be made to the conclusions of Eberhard Pinder, who performed a visual observation in 1955, complemented by infrared inspection. Pinder’s results were made known to card historians mainly through a renowned book published by the Museum.(4)

Let me use a table for comparing the two sheets in question: top Washington, bottom Leinfelden.

There is some minor inconsistency. Considering, however, the high uncertainty of the observations on the Leinfelden sheet, it becomes easy to suppose, as already did the several experts who described these sheets, that both sheets actually have the same figures.

I trust in Pinder’s study and feel certain that observing now the Leinfelden sheet with naked eyes cannot bring further useful information. I am only wondering whether in the labs of restoration of art works, or even of some police departments they have got more powerful tools in the meantime.

Comparison with other series of triumphs

The comparison with other sequences of triumphs has also already been done and clearly Dummett assigned this sequence to his A order, namely the Florentine-Bolognese order typical of minchiate and similar triumphs.

With respect to a standard tarot of 78 cards, with all three sheets with their 72 cards we are still lacking 6 cards: the four 10s, the Queen of Batons, and the Matto, whereas with respect to minchiate we have an additional Popess and more missing cards, as discussed below.

As far as the order of the sequence is concerned, the Table below compares it with other known sequences, adapting a similar list.(5) The same cards were sometimes differently called in these sequences, but I have adopted the same names for them. Moreover, I have listed the Rosenwald sequence respecting the order of position – thus putting the Ruota in a fairly uncomfortable position between Impiccato and Morte (which does correspond to its position in the sheet – I know that number 13 is traditionally assigned to Morte, but maybe this cardmaker did not respect the rule). Comparing with the other sequences of the Table, it is just the position of Ruota that appears to be much higher than usual.

Other differences are less pronounced with some cases of inversion within a couple of subsequent cards. Temperanza is, on the contrary, in its usual low position and it is in Marseille tarot that this card seems to be misplaced (often supposed to have been done to keep number 13 linked to Morte).

My Sheet 4

We can try and conclude for the moment that with the first two sheets we can already produce something useful, whereas with the first three sheets we neither reach a complete 52-card pack, nor a standard 78-card tarot: in any case, a fourth sheet is needed!

For this required Sheet 4 we can thus chose either one with four 10s for completing the 52-card pack or, better, one with these four cards along with the Queen of Batons and the Matto, in order to complete also a standard tarot pack. In conclusion, while we could compliment this cardmaker for suitably selecting the 3x8 system of the first two sheets, we find his fourth sheet with six cards at most rather deceiving.

Which was the ultimate reason of the 3x8 division of these sheets? It is impossible to find a convincing answer without looking at “my” Sheet 4. Using very little of my imagination, let me assume that Sheet 4 was exactly divided into the same 3x8 pattern as the three previous ones. It is easy to outline the contents of my Sheet 4: of the new three rows of eight cards, two and a half are allocated to the common 20 additional cards that distinguish minchiate from a standard tarot; the remaining half row is exactly required for the four 10s.

Unfortunately, in order to complete this hypothetical reconstruction two further bits of fantasy are needed. What we have got with the addition of my Sheet 4 of 3x8 cards is clearly a minchiate pack, but some adjustments are required, first of all because we still have one missing card: 4x28 cannot provide the 97 cards needed. (97 is even a prime number, which excludes any series of identical woodblocks.)

Apparently, the Matto is still missing, which might require a fifth woodblock for just one card. It appears too naive to imagine five blocks, with Sheet 5 devoted to a single card! My imagination prefers to suppose that minchiate were originally formed by 96 instead of 97 cards. While 97 is a prime number, 96 is (25 x 3), and can thus be divided equally in a lot of different ways. Lothar Teikemeier has even suggested a possible way to explain this: there was sometimes a "mixed" figure representing together Matto and Bagatto(6) - one can thus suppose that only after a while was this card split into the two later known ones.

With a hypothetical 96-card minchiate pack, the reconstruction is more plausible. We still find, however, a difficult problem to solve and unfortunately this regards Sheet 3, instead of Sheet 4. What our imagination suggests here (where its intervention is hardly allowed) is “simply” to exchange the existing Papessa with the missing Queens of Batons - it is however the Imperatrice here and not the Papessa who might better be used in the place of the missing Queen, having some similar features, scepter included.

To find an additional Papessa in a minchiate pack can be explained in several ways, either as a preliminary stage of the pack itself of minchiate, or in order to allow the pack to be used for playing ordinary tarot games, after discarding the 20 additional minchiate cards. This would however lead us to increase from 97 to 98 the cards of common minchiate instead of reducing it to 96 as done before.

On the other hand, I am not at all able to find any reliable justification for the absence of the Queen of Batons in any minchiate pack, as well as in any other pack of a similar family. Of course, it can be imagined to be present in Sheet 4, but this would require that another typical minchiate card, in addition to the Matto, is missing here.

We have already discussed the question in enough detail and any further discussion will hardly lead to the correct solution. A simple way remains to definitely solve the whole question: instead of my Sheet 4, one has simply to discover the true Rosenwald Sheet 4, and even – should this be the case – Sheet 5. If we are optimistic enough, we can wait for this event.

Conclusion

The Rosenwald sheets are based on a 3x8 structure of the playing cards to be produced. With two such sheets, we obtain a full pack of 48 cards (missing the 10s). With the 3rd sheet known we don’t obtain any complete pack. The required 4th sheet is not known and must be hypothetically reconstructed. One can suppose that it contained just six cards and thus both a complete 52-card pack and a standard 78-card tarot could be produced. More plausible appears, however, to envisage a fourth sheet with the same 3x8 rows. I assume that the three extant Rosenwald sheets, together with "my" fourth one, can give us an idea of the first pack of minchiate known. What seems probable is that this Florentine pack had initially one card less, 96 instead of 97 cards. This reconstruction is however not flawless, since it requires some adjustment for one or two cards of the pack.

Footnotes:

(1) Michael Dummett, The Game of Tarot. London 1980.

(2) Ross Caldwell, Personal communication, November 2011.

(3) Lothar Teikemeier, Personal communication, November 2011.

(4) Detlef Hoffmann, Margot Dietrich, Tarot - Tarock – Tarocchi. Leinfelden-Echterdingen 1988.

(5) Thierry Depaulis, The Playing-Card, Vol. 36 No. 1 (2007), pp. 42-43.

(6) Lothar Teikemeier, Personal communication, October 2011.

Pictures in better quality at article: Cristina Fiorini, The Playing-Card, Vol. XXXV No. 1 (2006) 52-63. Rosenwald Sheets, Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection, 1951.16.5; 1951.16.6; 1951.16.7;